Introduction: the mind and its states

Desires are mental constructs that become drivers of our actions and behaviours. Wishes and preferences that do not affect our behaviour are not so important. Of course we are seldom aware of what we do and for which reason. When we participate in a process of psychotherapy or analysis, one of the outcomes is that we begin to know our drives.

This might sound like a simple thing, but it is not.

Our mind hides most of our drives behind symbols. The symbolical encoding of our mind prevents us from actually understanding what we are doing. There are links in our mind and there is no semantic or linear consistency between what links to what. The mess that this connotes is a depiction of the flux called living.

But you might not feel messy. You might feel very sorted.

This is indicative of the internal state of your psyche and is not the external logic of perceiving the world.

When the overbearing feeling is being sorted, the messiness is being mistakenly or incompletely perceived as sorted.

Feeling messy or fragmented is generally seen as an opposite of feeling sorted. But it just represents different forms of perception.

The state of happiness represents an emotion that manages to see balance even in messiness. Messiness is prevalent throughout our lives and happiness is just a stage where we find meaning in it.

Once we find messiness meaningful, it is not perceived as being messy anymore. This is the idea enshrined in the idea “beautiful chaos”.

Feelings of messiness arise when we are forced to deal with more complexity than we have a capacity to process. But is this indeed messiness? It might not be. It might be something similar to the buffer in a computer program. What we process becomes coherent — rest remains a mess.

So that means that our work in life is to keep processing our feelings.

We do not always even know what we feel.

It is easier to think that we do things in an unfeeling way, purely rationally than to think that our actions are motivated by our dynamic feelings. If we believe the latter then we have the additional responsibility of not just being constantly aware of our feelings but to also make sure that our feelings are not short-circuited.

What are circuits in the context of our feelings and our behaviour? And what are short-circuited feelings?

The circuits in the context of our feelings and behaviour (behavioural circuits) are systems which connect our will (to do), our desire (our wants), our emotions (our feelings) and our act (our external facade).

When feelings and the actions that follow them (our emotions, our desire and our act) do not connect directly, our behavioural circuit is short-circuited. Such a circuit is very unpredictable and unstable. Desiring linear outcomes at such a stage is unrealistic. Feelings and actions can get oriented towards different goals.

How does this dis-orientation happen?

We will not got into how this dis-orientation happens but we will examine what are effects of such a dis-orientation when it does happen.

Effects of a Dis-orientation of Feelings and Actions

A dis-oriented mind is not competent to function in the real world. A person with such a mind is likely to develop dependencies & anxieties. Such a person might also have a hard time retaining their focus and getting things done.

So what is to be done?

I haven’t progressed down this path enough to recommend solutions. My behavioural circuits often get short-circuited and am able to start functioning again only with some difficulty. Observing myself reveals what is happening and how it is unravelling. But not without the help of a psychotherapist…

I lead an active social life. Others have expectations from me and judge me like they would anyone else. And why shouldn’t they?

People like me are not broken enough to be fully dysfunctional. I am always in the grey area of being perceived as intelligent but also being perceived to be difficult to work with. I am neither clever enough to be quickly successful and nor stupid enough to be useless.

So what is the way for me to explore and develop my potential?

Making Progress: In Life & Work

The perception of progress might be understood to be a matter of perspective. It might be thought of as subjective. In the social environment that we live in, it might well be so too. But from the developmental psychology — the concept of progress is pretty absolute.

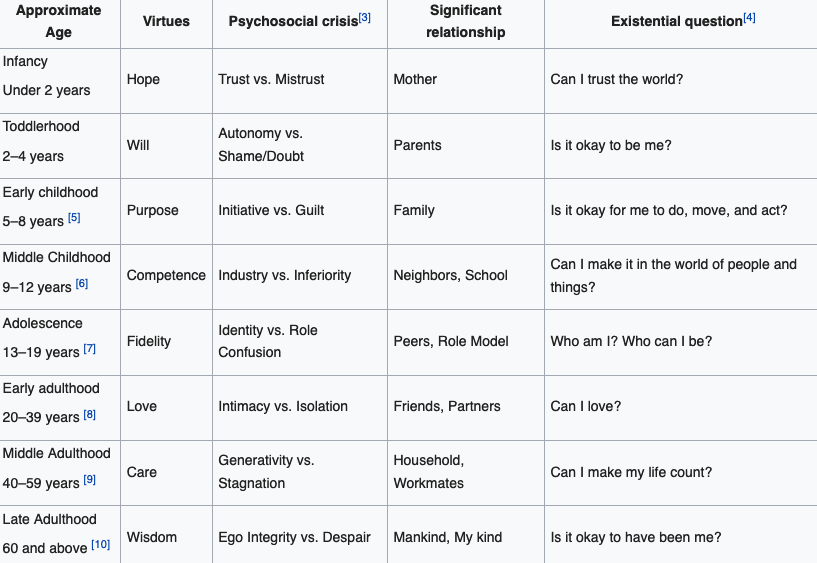

Developmental Psychologists Erik and Joan Erkinson outlined a life-cycle approach detailing the psychological development of individuals.

This model suggests that different psychological developmental stages have a different existential question associated with them. Different existential questions probe different dimensions of the idea of progress.

Existential questions and the kind of progress they are anchored to:

(infant) Can I trust the world?

(idea of progress) Independent exploration of the world

(toddler) Is it okay to be me?

(idea of progress) Validation from the world for the self

(early childhood) Is it okay for me to do, move, and act?

(idea of progress) Validation from the world for one’s actions

(middle childhood) Can I make it in the world of people and things?

(idea of progress) Validation from the world for one’s intentions and value

(adolescence) Who am I? Who can I be?

(idea of progress) Self-knowledge is oriented towards making choices

(early adulthood) Can I love?

(idea of progress) Extending the notion of the family and of loving

(middle adulthood) Can I make my life count?

(idea of progress) Wanting to leave behind a legacy

(late adulthood) Is it okay to have been me?

(idea of progress) Evaluating one’s legacy

These notions of progress encapsulate the changing nature of our drive to find resolution and closure in life. Unlike what Erkinson suggested and what the above table communicates, I do not feel these developmental stages are organised neatly across our physical age. When this model (called the life-cycle approach) is looked at as a set of ideal benchmarks, it starts to make more sense to me.

Each of us has developmental gaps. As per the narrative of these gaps, different parts of us are stuck at different ages.

Rare, mentally healthy individuals are whoever they seem to be. They are the age they represent. None of their developmental stages are stuck at points in the past.

If an individual is all caught up with the past, the future and the present do not hold such challenges. These rare mentally healthy individuals are the sages and the pillars of families and societies.

To make progress in life and work means to catch up with ourselves. To catch up with our time and to be fully here. This is easier said than done and is a process. A process that is sometimes long and difficult.

Why and how do these developmental gaps emerge? Why don’t we have some kind of a guiding system to know when we are laying the foundations of a conflict? Conflicts mature and develop into full-fledged gaps.

Of course this is wishful thinking and this cannot happen. Conflicts and the developmental gaps they lead to and the effort to cover these gaps provide narrative support and the flow of motivation to our lives. So we cannot wish these away.

The Emergence of Developmental Gaps

Developmental gaps emerge when the messiness we spoke of earlier accumulates layer upon layer and is not processed or parsed. Most schools of spiritual thought talk about the harmful effects of being overly busy. Being busy is not about having a lot of things to do. It is about living in a way that the things one has to do all seem to be of the highest priority. It is not important to understand whether one has seemingly important things to do or not.

If one is honest one will do all of one’s work importantly. Doing things importantly means to give the tasks the attention they need. Of course it might seem difficult to give mundane tasks any kind of attention at all. But the point is not to give attention, it is to be attentive. When the focus shifts from doing to being, it becomes possible to take on the onus of transformation more easily.

Personal development has a lot to do with one’s self-image and one’s self-image is not always consciously adopted. Sometimes we internalise other people’s impressions of us at a formative age or at a vulnerable moment.

We are motivated to act, react and sometimes also not act appropriately because of what we think about ourselves. What we think about ourselves and what we are are of course are two different things. The latter we might never ever know…

Precisely because we might never know who we are, what we think of ourselves matters a great deal. What we do in life adds to the data of what we think about ourselves. And this story becomes more and more layered…

The self-image that we identify with is always flawed. The degree of its flawed nature will depend on how far we have traveled on the journey of self-discovery.

So, a big developmental gap that is almost consistently and universally occurring in human society is in relation to our self-image.

For instance, I spent my youth working and did not have a peer group or other young friends. Part of the reason for this was that when I was younger I had the self-image of being an older person. This led to me feeling isolated and sad. I felt like I was the odd one out in most social groups.

My self-image was of an older person because of my previous experiences and trauma. Besides other things I had already gone though an intense heartbreak and a suicide-attempt at the age of 19. Trauma immediately makes you feel older and dis-oriented. Be it physical or emotional. Trauma forces you to experience things that otherwise you would not feel at all. Adolescence is so far away from infant-hood that its memories have faded. For kids who have not even suffered high school bullying, there is no common ground for them to understand or make friends with someone who has experienced any other more elaborate trauma.

Now, when I am much older, like most middle-aged men my self-image is of being a much younger person. This leads me to sometimes desire the friendship of younger people. But this can only be awkward and strange for them. It can rarely work out. Expecting that the truly personal should step out of concepts like age is difficult.

So I feel isolated and sad about this sometimes. Mis-placed self-images all throughout life have led to these developmental gaps. Development gaps related to one’s self-image involve one kind of effort to acknowledge but altogether another kind of effort to correct.

I don’t know how the process of bridging developmental gaps goes as I have not been able to bridge mine so far. I have not even identified all of the gaps in my personality yet. But I understand that this perspective exists and is relevant.

Conclusion

Messiness represents a state of unfamiliarity and according to most discourses on creativity, this is a good thing. If we constantly see the world as something we don’t know rather than the assume that we do know it then we stand to discover more.

From personal experience, I would say that the perception of messiness is supportive to the identification of developmental gaps in oneself. When I perceive my word as messy, I search for ways of sorting/organising it more. Then I observe and try to identify factors that do not support the further organisation of my mental and psychological information. Then I identify developmental gaps — usually with some help from someone else.