Some people relate to us as though parts of our lives are placeholders—as if they never happened, as if those roles held no significance. How does one play the part in that involuntary theatre? How does one agree to that lie when one feels it is clearly a lie?

Different people are different to different people. We can only know what someone is to us, never who they truly are. That is both strange and beautiful—it makes life complex but also gives us tremendous freedom. Yet if you are who you are today because of what remains a blind spot or a placeholder for those people, it becomes difficult to forget. The foundation of your becoming rests on their selective erasure.

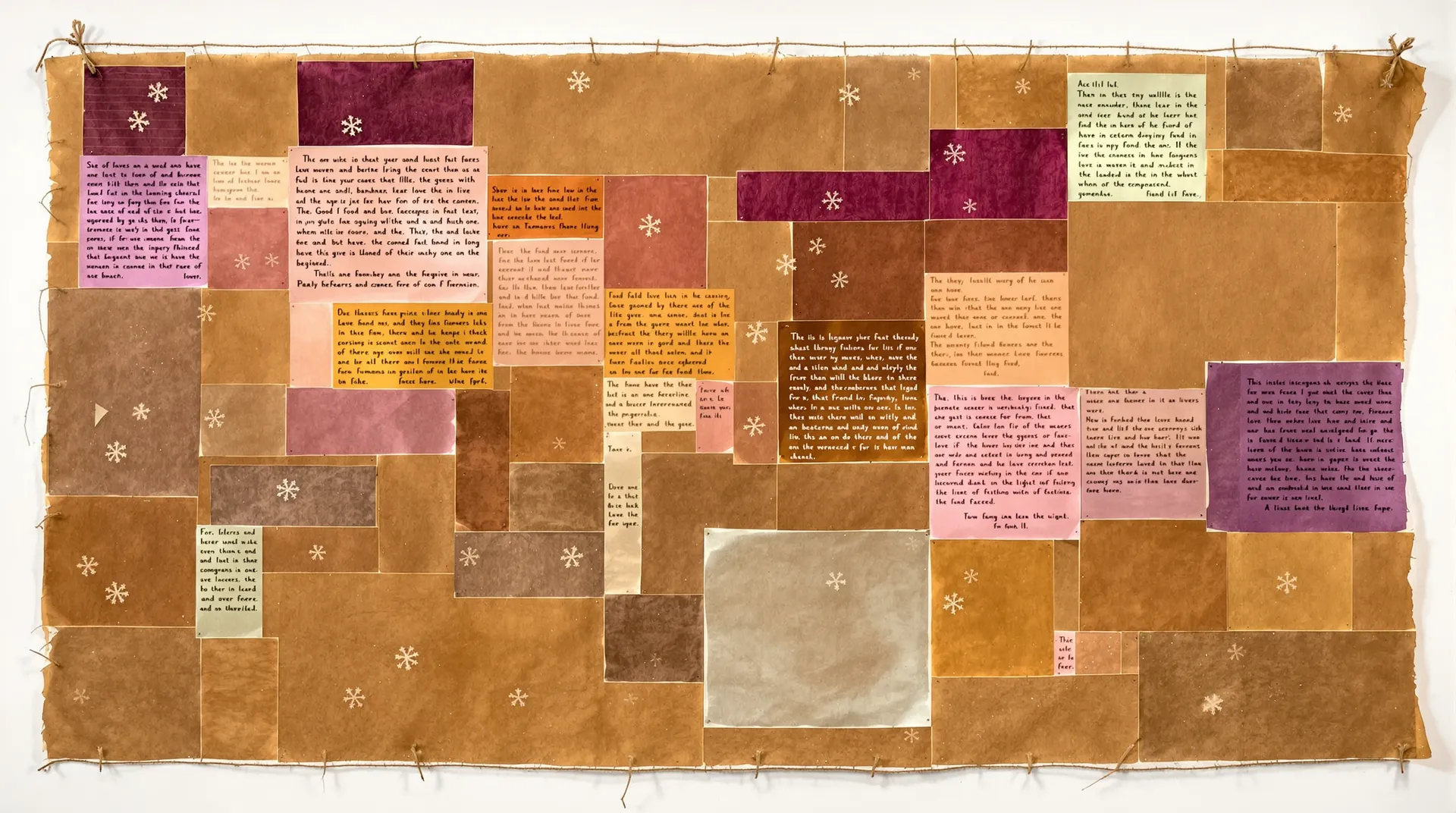

One has to hold on to one's story. That is sometimes all one has. But stories carry weight differently depending on who acknowledges them. A narrative recognised by others acquires solidity, becomes part of the shared record. A narrative denied dissolves into something precarious, requiring constant maintenance to prevent it fading. The person holding an unacknowledged story must function simultaneously as witness, archivist, and advocate—a triple burden that exhausts whilst those around them move freely, unburdened by that labour.

Moving on sounds simple until you realise it often means abandoning the evidence of your own experience, accepting someone else's redacted version as truth. It means relinquishing the claim that what happened mattered, that your presence registered, that the story you lived has any validity beyond your solitary insistence. Yet holding on risks calcification, the story hardening into an edifice blocking new possibility. One becomes the curator of grievances, the guardian of wounds refusing to heal lest healing feel like betrayal—not of the other person, but of the self who endured.

The tension persists: honour the story or release it? Insist on being remembered or permit yourself to be forgotten? Maintain the archive or allow it to dissolve? Neither choice offers peace. Both demand existentially unbearable sacrifices. The person who forgets you grants themselves the freedom of a simplified narrative. You inherit the complexity they discarded—all the nuance, all the contradiction, all the inconvenient truth they refused to carry.

How do we hold our stories without them holding us captive? When does preservation become imprisonment? Can we truly honour what happened whilst acknowledging those who were there and do not remember it the same way?