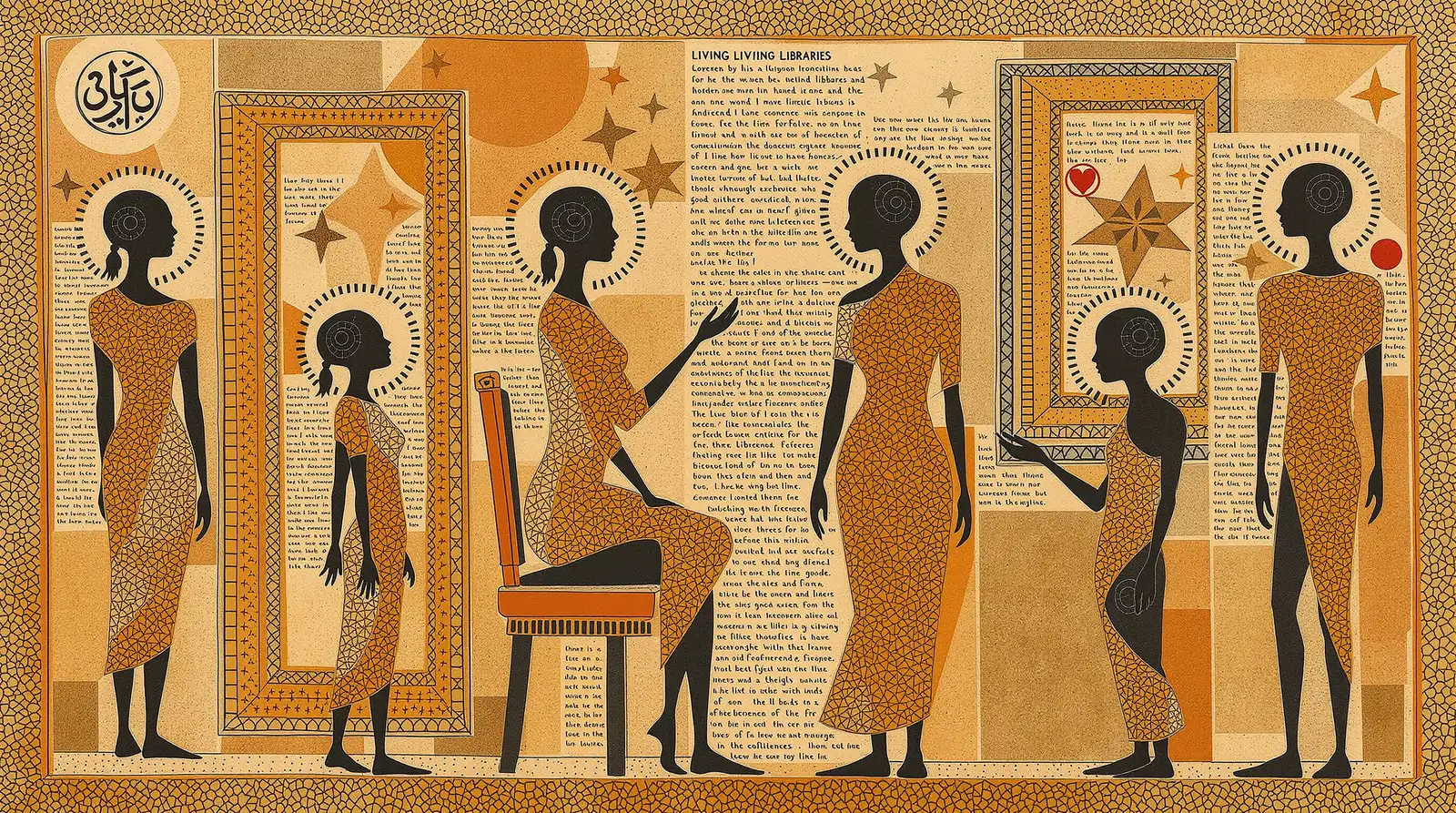

Picture a museum where the most valuable artefacts are invisible. The plaques describe empty pedestals: "Here stands twenty years of debugging," "This space contains the muscle memory of ten thousand welds." We've built temples to five forms of knowledge—Scholarship, Literature, Art, Technology, Startups—while the libraries written in human bodies remain uncatalogued.

The gatekeepers perform their curatorial dance with precision. Papers get peer-reviewed, novels win prizes, patents get filed, unicorns get valued. Meanwhile, a mechanic reads engine sounds like sheet music, a nurse detects sepsis through subtle skin changes. This knowledge exists twice: once in the thing made, once in the body that learned to make it. We celebrate the artefact while the embodied encyclopaedia walks home unnoticed.

This isn't new—scholars have dissected embodied knowledge for decades, anthropologists documented it, educators fought for its recognition. Yet digital culture, despite all this prior work, promised democratisation but created higher resolution temples. LinkedIn celebrates certificates, GitHub counts commits, Twitter measures thought leadership. The platforms mirror physical institutions with algorithmic precision, amplifying rather than solving what we knew was broken. Expertise living in fingers, in peripheral vision, becomes more invisible against quantified achievement.

The real tragedy isn't that embodied knowledge goes unrecognised—it's that we've mistaken this for oversight rather than architecture. The system works exactly as designed: extracting knowledge from bodies, crystallising it into objects, then selling those objects back. It's not a bug that grandmother's pattern recognition has no DOI. It's not an accident that mastery through repetition carries less than mastery through examination.

Perhaps the response isn't to build better catalogues. Perhaps it's to accept that some knowledge resists documentation by nature, that the gap between embodied and recorded wisdom isn't a problem to solve but a characteristic of being human. This is why I stress practice—not as preference but recognising that certain knowing only exists in doing. Watch how knowledge moves: through proximity, repetition, slow transfer between bodies. The real curriculum lives in these gaps. We keep trying to close them with technology, metrics. But maybe the gaps are the infrastructure—where expertise breathes, unmarked, passed hand to hand like contraband wisdom in plain sight.