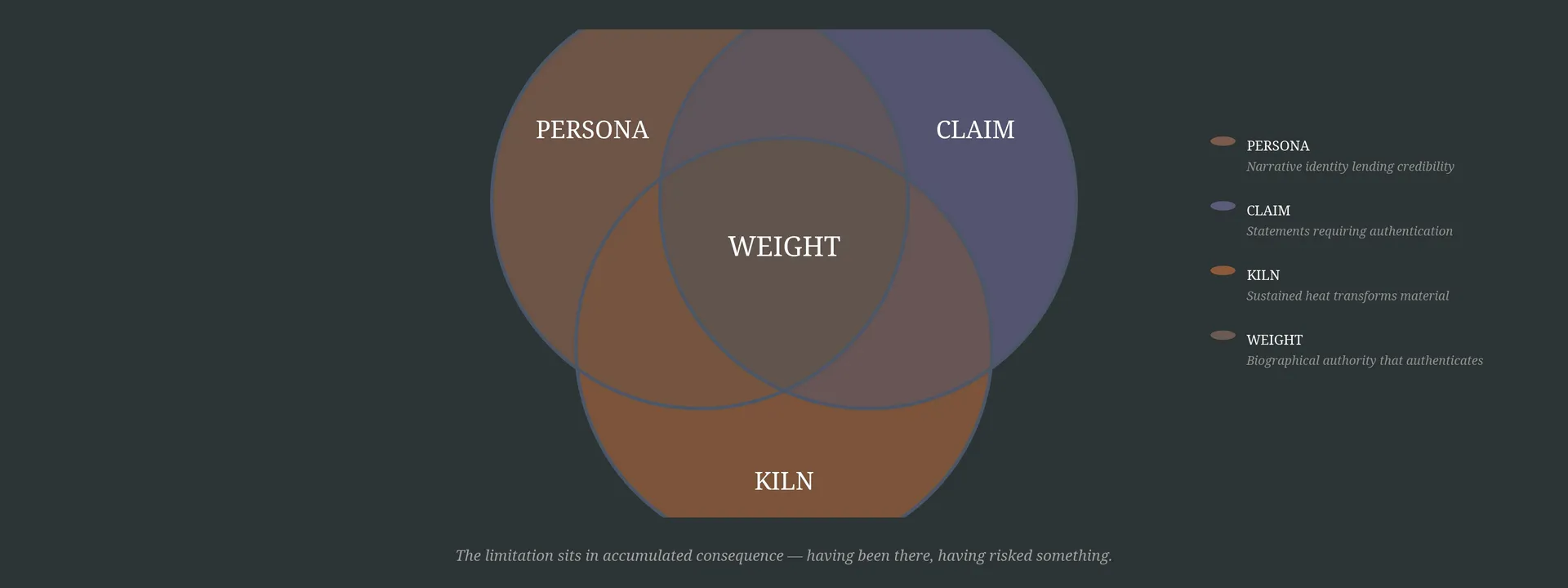

The permanent limitation of any generative system is the actual personality and the life-experience of the user. Why? Because even if the sound is generated, unless it is given a voice by the user's persona, it does not become real. Everything that is generated has to be within the scope of the narrative persona of the user. The narrative persona makes a generated claim sound like a real claim by lending the claim a certain amount of plausibility.

So to make sure someone is authentic we need to know the person well and not just verify the claims they have made. The syntactic quality of the language might not have anything problematic—the inability of the narrative persona to lend credibility to the claim might actually point to one.

Think of voice authentication systems at banking institutions—they verify identity through acoustic signature: pitch, timbre, speech rhythm. What makes those patterns yours isn't the waveform—it's decades of biological and cultural shaping. A generative system could replicate your frequency profile perfectly, yet the claim rings hollow without biographical weight. Authentication fails not in the sound but in the accumulated consequence.

When someone declares "I've spent thirty years studying glacial dynamics," conviction comes not from syntactic correctness but from lecture scars, funding rejections, field journals stained with ice melt. These experiential sediments bond claim to claimant. We mistake this for a technical problem. But the limitation sits elsewhere. Narrative persona functions like a potter's kiln: it doesn't merely shape clay, it fundamentally alters material through sustained heat.

Consider how metallurgists distinguish genuine antiques from reproductions: not through visual inspection but through metallurgical biography. Genuine bronze develops oxidation patterns, crystalline structures betraying centuries of temperature fluctuation. Forgers replicate surface patina exquisitely, yet interior architecture reveals itself—it hasn't lived through claimed centuries. The metal's history is written in molecular structure, not appearance.

This creates peculiar tensions. We build systems generating plausible content whilst eroding conditions that produce genuine plausibility. The user's narrative persona becomes the sole authenticating mechanism. Yet we train ourselves to trust generated fluency over biographical authority.

Where does authentication migrate when claims become indistinguishable from credentials? Perhaps it concentrates not in what someone says but in who they demonstrably are—in having been there, having risked something, having changed. Perhaps we've confused verification with knowing all along.